For the man who won 77 of the 80 races he ran, Milkha Singh has no medals. It has been some years that 'The Flying Sikh' donated his sporting treasures to the nation. No personal souvenirs line his living room walls, no trophies sit on the mantle. Instead, the walls make do with pictures of the surgeon in America who saved his wife's life and Havildar Bikram Singh, a Kargil martyr.

"I have given permission that my medals be transferred from the Jawaharlal Nehru stadium in New Delhi to the sports museum in Patiala," says the 72-year-old Singh. Strangely, the stadium gallery lined with many of India's sporting talent does not have a single picture of Milkha Singh. In a country where great sportspersons are few and far between, India has a strange way of honouring its stars.

Milkha Singh's achievements can do without such testimony. "The people of this country remember me. I may have started dyeing my beard but I am recognised at airports, railway stations -- anywhere. School textbooks have chapters on me, and somehow the sobriquet 'The Flying Sikh' has endured in people's memory," he says

Singh, however, has no complaints about the recognition given to him by the government. A Padma Shri winner, the legendary athlete who started his career on a Rs 10 wage went on to become director, sports, ministry of education in the Punjab government. "I have received more than I deserved."

It was a hard uphill climb for the refugee from Muzaffargarh in west Pakistan. The Partition massacres of 1947 took the lives of his parents and Singh was rejected by the army thrice. He subsequently enrolled in the army's electrical mechanical engineering branch in 1952 when his brother Malkhan Singh put in a word for him, and experienced his first sport outing at its athletics meet a fortnight later.

"That was the first time I saw a ground bedecked with flags," reminisces Singh. "I later participated in a crosscountry race with 300 to 400 jawans. And sat down after the first half mile before starting again -- that was my first race."

Determined to be the best and realising his talent as a sprinter, the jawan took to training five hours every day. Motivated by his coach Havildar Gurdev Singh, he left it to the elements to hone his craft -- running on the hills, the sands of the Yamuna river, and against the speed of a metre gauge train. He says so intense was his training that very often he vomitted blood and would collapse in exhaustion.

Every morning Milkha Singh still goes for a jog by the Sukhna lake in Chandigarh. Most afternoons are spent playing golf and he uses the gym in his house regularly. "Discipline. You have to be disciplined if you want to be world class," he says, "That's what I tell my son Jeev. I give him the example of Tiger Woods, and hope he would bring the medal I couldn't."

Jeev Milkha Singh, India's best golfer, was recently awarded the Arjuna Award and is striving to make a mark on the international golf circuit. Whether he does manage to bring the sporting glory that eluded his father, is yet to be seen. Till then, it is a disappointment that Milkha Singh will never forget. Forty years on, that failure in Rome still haunts him.

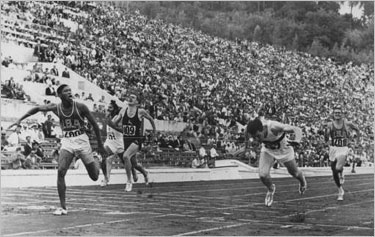

After clocking a world record 45.8 seconds in one of the 400 metres preliminaries in France, Milkha Singh finished fourth in a photofinish in the Olympics final. The favourite for gold had missed the bronze. By a fraction...

"Since it was a photofinish, the announcements were held up. The suspense was excruciating. I knew what my fatal error was: After running perilously fast in lane five, I slowed down at 250 metres. I could not cover the lost ground after that -- and that cost me the race."

"After the death of my parents, that is my worst memory," says Singh, "I kept crying for days." Dejected by his defeat, he made up his mind to give up sport. It was after much persuasion that he took to athletics again. Two years later, Milkha Singh won two medals at the 1962 Asian Games. But by then his golden period was over.

It was between 1958 and 1960 that Milkha Singh saw the height of glory. From setting a new record in the 200 and 400 metres at the Cuttack National Games, he won two gold medals at the Asian Games at Tokyo. The lean Sikh went on to win gold at the Commonwealth Games in Cardiff, and was awarded the Helms trophy or being the best athlete in 1959.

Three years before the Indo-Pak war of 1965, Milkha Singh ran that one race which made President Ayub Khan christen him 'The Flying Sikh.' His defeat of Pakistan's leading athlete and winner of the 100 metres gold at the Tokyo Asiad, Abdul Khaliq, earned him India's bestknown sports sobriquet. "It has stuck since," he adds.

Thirtysix years later, Britain's Ann Packer remembers him too. This time for his camaraderie. Jittery about her performance in the 800 metres against formidable French German and Hungarian athletes in the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, Packer clearly remembered her encounter with Singh in the lift they shared on the day of her event. 'Ann you vill win,' she recounted Singh's words to a The Sunday Times journalist at her home in Cheshire recently.

And vin she did. Packer clocked 2min 1.1 sec and set a new world record. Singh was among the first to congratulate her.

There are many who still congratulate Milkha Singh. "Sirji, I remember seeing you when I was a young recruit in the army," said Gairwar Singh as he chanced upon the former athlete getting into his car outside the Chandigarh Golf Club. Elated that Singh stops to shake hands with him, Gairwar Singh -- now a driver with a transport company in Delhi -- tells him about his interest in wrestling.

"It is appreciation from the people that helps me go ahead at this age," Singh had earlier said at his home in Sector 8. With two of his daughters married and one away in the United States, and his son travelling around the world regularly -- Singh says he enjoys the tranquility. Last year, he adopted the seven-year-old son of Havildar Bikram Singh who died in the Battle for Tiger Hill. The child is at a boarding school and Singh has taken on the responsibility of bringing him up.

"We owe it to those who have died for the honour of our country," he says, "Unlike our cricketers who have sold our country." Deeply disappointed with these ambassadors of India's most popular game, he firmly believes the guilty should be punished. "They cannot mock the aspirations of an entire nation," says Singh surveying the debris of many a fallen sporting icon.

Decades after he hung up his running shoes, one thing is for sure -- the Flying Sikh still stands tall.

******************************

Jeev Milkha Singh on his father:

Whenever I look at Milkha Singh, I see a dedicated and determined human being. He enforced strict discipline in me in particular and was very tough at times.

He wanted me to become a better golfer. There is no way I can match him in any manner. I have always looked up to him for what he has done for the country. He is a great motivator and if anyone takes his advice he is bound to excel in life.

I was not even born when he quit running. This is my biggest misfortune. Of course, I have seen him jogging on the golf course to warm up before a game. I have watched some of the documentaries made on him and I am really impressed. It was nice to see him in action. To realise that 'The Flying Sikh' is none else than my father. I wish I had seen him participate in a competitive race in a stadium though, than see him on film.

I was 11 when I went to boarding school in Shimla. I had hardly entered my classroom when I heard a boy telling another boy that I was Milkha Singh's son. When I heard this, I realised my father was a big name in Indian sport. Till then it had never ever dawned on me that he is a legend.

He is a frank human being, a no-nonsense man, who does not take no for an answer. At 72, he still has the same drive. When I play golf with him, he wants to beat me. The zeal to be better than his opponent is still there. Like great athletes he believes there is nothing in the world you cannot achieve provided you have the will to do so.

If I were asked to list five of his great qualities, I would say he is honest, focussed and knows his goals. He has the determination to achieve his goals and has great motivation skills. Even an ordinary player can be moulded into a good one under his guidance. Last, but not least, he is a very disciplined human being.

He says if you have achieved one goal, then you should set your eyes on higher goals and continue your drive to do better and better. "If you have become the best in Asia, then you should try to be the best in the world" is what he tells me all the time.

He wanted me to become an athlete. But I wanted to play golf like he did after giving up athletics. He told me he had nothing against my playing golf. But he told me, "Son it is no use playing golf if you are not going to be the best. Whatever game you may play, you have to prove that nobody can beat you." When I am not doing well, he encourages me to do well. He has been a great source of inspiration.

But even Milkha Singh has his regret. Even now, he cannot forget the 400 metres at the Rome Olympics where he finished fourth in one of the most competitive races -- all four runners broke the world record and finished the race in four minutes. He is going to die with this regret at the back of his mind. Sometimes he becomes very emotional about this.

Milkha Singh is born once in many generations. I am lucky to have been born in his family and watch him from close quarters as his son.

No comments:

Post a Comment